Art in Context lecture: What Binds Us Tight

submitted by the Sordoni Art Gallery

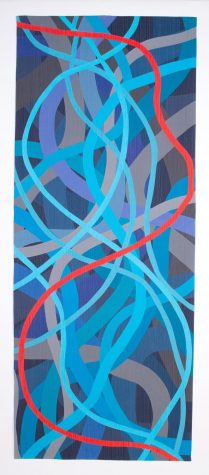

“Things Fall Apart” by Mary Lou Alexander, shibori and overdyed cotton fabric using Procion MX dyes, wool batting and cotton thread.

On Jan. 30, Eva Polizzi, fibers artist, presented at the Sordoni Art Gallery. The lecture, “What Binds Us Tight,” was part of the opening reception of the new exhibit “Material Pulses: Seven Viewpoints.”

Many female artists who work in fiber arts are often overlooked by curators and museums. The lecture explored the history of fiber art and highlighted several women fiber artists, such as the Gee’s Bend quilters from Alabama and Louise Bourgeois.

“Eva is someone I met at the Wyoming Valley Art League and she had an exhibition there maybe one or two years ago. Her work integrates fiber techniques with fired clay and it was really beautiful and fascinating. I was really enamored with her work and so much so that I wanted to learn more about her,” said Heather Sincavage, assistant professor and Sordoni Art Director.

Polizzi had a mission of educating people about the history of fiber arts, describing how quilts were made in three parts: the backing, the padding in the center and then the top, which was often purely decorative. She discussed the fiber arts, specifically quilt making from a global perspective. She noted many women who made these pieces were often not credited.

“She really threaded the needle, taking us completely through the craft world, the utilitarian world and then took us into the fine art world, which I thought was really lovely,” said Sincavage.

“Mitote” by Denise L. Roberts, hand-dyed cottons, cotton batting and cotton thread.

She explained how almost 4000 years ago, weaving was developed as sewing plant fibers together to make cording. Early needles were made from bone, the thread was made from either vegetable or animal fibers, and natural dyes were used for color. Many of the quilts designed at this time were rough and not comfortable, but they were an alternative to wearing animal hide.

“Many people don’t [see fiber weaving as an art form] as it’s been drilled into their heads over the years that it’s just a craft, it’s just a hobby. But there’s certainly an art form to it and on the flip side of it, it’s also somewhat political,” said Sincavage. “The fact that this is considered women’s work or work of African-Americans was always thought of as somewhat less valuable. Whereas it takes a lot of skill to be able to craft something well, and then to also craft it beautifully so it doesn’t deteriorate over time.”

Women eventually learned how to loom wider cloth and create massive clothing. Ornately patterned textiles were made using plant dyes and were very colorful. Polizzi then discussed Japanese boro textiles, where multiple layers of pieces of cloth were stitched together. This was done to preserve any and all scraps of fabric and prevent throwing anything away.

These textiles were reused in a utilitarian fashion, sometimes incorporated into other fabrics until they completely fell apart. Many of these textiles were made with a running stitch, which was a singular thread holding together many layers of cloth.

These stitches were used to make patterns that represented anything from prosperity and health to good luck. Although the original purpose of these quilts was utilitarian in nature, they evolved over time into an art form.

“When we look at fiber art, when we can see it, the evidence of the hand and their heart and soul, it’s putting material into something sublime,” said Polizzi.

She then discussed the Gee’s Bend quilters from Alabama, where shortly after the Civil War, former slaves remained as farmhands and made huge, large scale quilts. Some of these were able to fit king-sized beds, but they were not used for bedding.

“Momentum” by Christine Mausberger, suspended strips of rubylith, tulle and thread.

In the 1900s, many of these women did not go to school, and they continued to make these quilts in the traditional way from their mothers and grandmothers: not stretched or hung but crafted in their laps. No two quilts could be found exactly alike. Unfortunately, many were eventually burned or thrown out.

In the 1960s, some went to New York City, and department stores wanted their quilts. Many of the original quilters were poor and were offered money by these stores. After a short time, many of them quit.

“It’s their personal narrative, their history. They didn’t want rich white men telling them what their history was,” said Polizzi.

She concluded the lecture by speaking about artist Louise Bourgeois, who had a very long career in fine arts before concluding her career in fiber arts. Although known for works such as her spider sculptures, Bourgeois later worked on projects such as sewing books together, some of which had words.

“I’m always really interested in showing aspects of the art world that are underrepresented. While we try to do household names from time to time, I think it’s just as important, especially as a university, to fill in the gaps and make other art forms and artists household names. And that’s by educating people and bringing their awareness to that kind of work,” said Sincavage.

The lecture marks the kickoff for “Year of the Vote: Gender, Politics, & Power,” a year-long event that celebrates the 100-year anniversary of women receiving the right to vote.

For more information about the exhibit or Year of the Vote, please follow the Sordoni Art Gallery on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter, or contact Heather Sincavage at heather.sincavage@wilkes.edu.

Parker Dorsey is a senior communications studies major with a concentration in strategic communications. Parker began as a staff writer for the opinion...